There Is Nothing Funny About Peace, Love, and Understanding

A primer on Leading with Love, with a little help from Elvis Costello

As I walk through this wicked world

Searchin' for light in the darkness of insanity

I ask myself, "Is all hope lost?

Is there only pain and hatred and misery?”

And each time I feel like this inside

There's one thing I wanna know

What's so funny 'bout peace, love, and understanding?

- Nick Lowe (1974), as recorded by Elvis Costello (1978)

[Note to email readers: this is a long post and may be truncated by your email server. You may want to read it on the Substack website, instead.]

It’s been a few weeks since I’ve written on the topic of Leading with Love. I originally planned today’s essay to be the 3rd or 4th one I published, but the muse and current events pointed me elsewhere. Now, I’m happy to return to the story of how I took my first steps towards Leading with Love, and hopefully, provide you with some tools and insight to do the same.

Below, I present an online conversation with a friend—we’ll call him Fred—who is on the opposite end of the political spectrum from me. He is a staunch supporter of the current president; I am decidedly anti-this regime. We’ve occupied these positions for at least the past ten years, when DJT announced his entry into the 2016 presidential race, if not longer.

The seeds of our conversation began when I re-shared a post on Facebook regarding the horrific torture and death of transgender teen, Sam Nordquist. It was a decidedly reactive post, and in my commentary on it, I cast blame for Nordquist’s murder on the 47th president, and more broadly on Republicans who still support him. I could have been more tactful in framing this post, but anger was in the driver’s seat.

Fred got active in the comments. He did so in a way that was neither aggressive nor accusatory, merely curious. This allowed me to hear a question, rather than a challenge. We went back and forth a bit, questioning each other’s interpretation of Executive Orders I considered to be anti-trans, and he did not. I desperately wanted my view to be the correct one and for him to acknowledge that. So, I pushed my point, attempting to be persuasive, and probably coming across as lecturing or self-righteous.

But my words, though finessed, felt like blunt instruments. Nuance was an elusive fawn. Eventually, we agreed the issue was far too complex to fully explore in the comments section of a Facebook post. Rather than continue to try to sway each other in an online public forum, we parted peacefully.

The weight of this conversation, as well as other aggressive and accusatory stances I had taken with Republican friends, pressed on me the next day. I was unhappy with how I’d behaved online; how I’d been willing to paint—with one, broad, monochromatic brushstroke—people who viewed the world through a different political lens than I, as wrong, as enemies, without even trying to hear their perspectives.

That behavior is the exact opposite of how I try to behave in my professional life as a social worker. It is the exact opposite of the principles I try to instill in my students as I prepare them to enter the field: approach conversations with curiosity, seek to understand a person’s subjective world view, be open to new perspectives, treat everyone with dignity and respect, and recognize each person’s inherent worth.

Instead of heeding my own words, I was allowing anger, rage, and frustration to devour me. I was reactive. Agitated. And, I realized, acting (and reacting) out of fear and a false need for self-protection.

Why?

I grew up with a very hostile view of the world. The world was presented to me as dangerous and threatening. It’s a piece of intergenerational trauma many Jewish Baby Boomers and Gen-Xers grew up with as the first post-Holocaust generations. That sensitivity was further complicated by other traumatic events experienced by my immediate family.

Also, I generally expected to be treated poorly by people, particularly my peers—put down, bullied, and dismissed, as was my experience in my youth. My sense of self was unstable. I often felt attacked by others, at least, that was my perception. As an internalizer and introvert, I tended to avoid confrontation. As a gentle male and Highly Sensitive Person, I was particularly vulnerable. As such, I was always on the defensive, particularly with those who challenged my beliefs and opinions in any way.

I realize now this was a very constricting way of being, leaving no room for the authentic expression of myself in the world. Of course, I desired to be seen and appreciated, but why would I take the risk when I expected evisceration?

In fact, I would eviscerate myself before others could do it to me. Tear myself down. Doubt myself. Hide.

This is probably why none of my ventures, creative or otherwise, got beyond the idea stage. It’s probably why I kept most people at a distance and let friendships fade. Why no matter how much success I found, I still struggled in every job. Why nothing I did could ever satisfy my own expectations.

Self-evisceration, at some level, was safer than risking exposure.

Regardless, my recent ponderings allowed a shift in my perspective. I realized that because of my fear of the world, distrust in others, and the need to self-protect, I wasn’t treating people the way I wanted to be treated—or even the way I actually wanted to treat them.

I was treating people the way I expected them to treat me.

Once I realized that, I knew it wasn’t how I wanted to exist in the world any longer. I was determined to be better.

The next time I saw a political post from Fred, it still triggered me. But rather than respond to the trigger with dismissal or aggression, I paused to consider how I would advise a student to respond. How would I respond if I truly sought to live my professional values?

I realized that if I viewed my response to this post as an opportunity rather than an attack, I would have freedom and flexibility in that response.

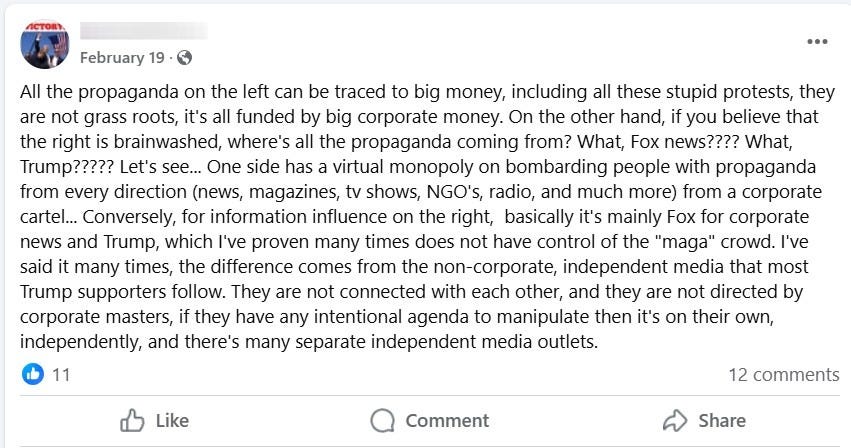

Here’s Fred’s post:

I commented on his post, setting the tone for discussion with curiosity, inviting conversation with the intent to bridge division and difference. I didn’t tell Fred what I thought. Instead, I sought to understand what he was thinking:

I was heartened to see my outreach met with positive feedback and a respectful, open response. The hearts and thumbs-ups from onlookers provided further encouragement.

I should take a moment to explain my relationship with Fred. He and I grew up in the same neighborhood and were close friends in elementary school. We drifted apart in middle school, as tends to happen. We barely saw each other in our pre-teen and teen years. We still have not seen each other or spoken in person in more than 40 years.

When I joined Facebook, the algorithm recommended Fred as someone I might know. Recognizing my childhood pal, I sent a friend request. I think we spoke briefly via Facebook Messenger to reminisce about our shared childhood. That was it. Calling us Facebook friends was a misnomer. At best, we were Facebook distant acquaintances.

Over the ensuing years, Fred posted topics and opinions to Facebook with which I disagreed. I generally did not respond, but over time, I still came to label him in my head as “adversary.” I judged him based solely on the content of his feed. I looked no deeper. That was all I sought to know of him.

This was the state of our relationship when I made my initial outreach.

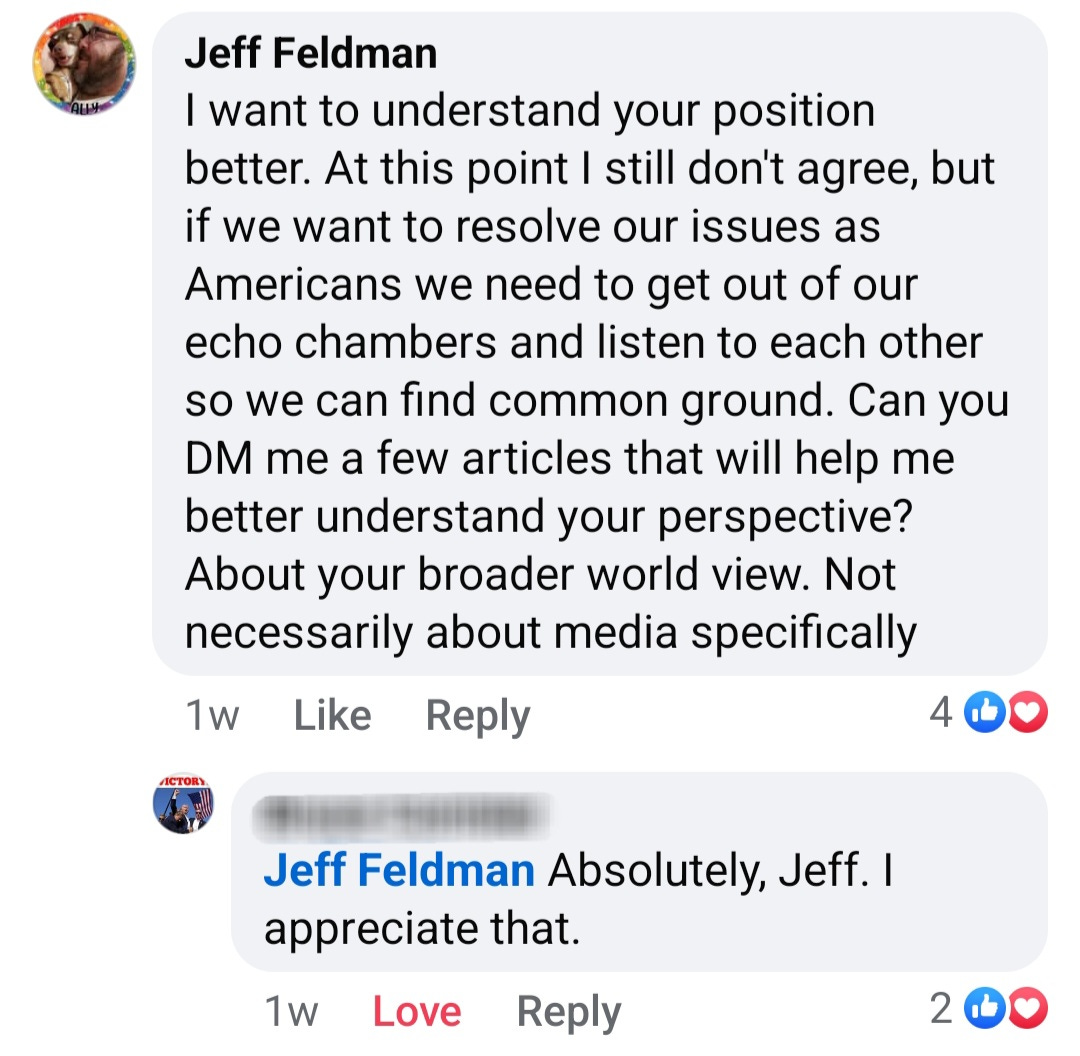

Fred responded via Facebook DM a couple of days later:

His response was polite and friendly. This emboldened me and set me at ease. I decided to continue to approach the discussion, not just with curiosity, but as a friend:

My approach seemed to be yielding results. It was empowering. My mind was in full gear, analyzing my entire past approach to political conversations, online interactions, my underlying hostility to ideas and beliefs that differed from mine, and the realization that despite considering myself open-minded, my mind (and heart) could be very closed.

Confidence growing, heart open, I let loose the flood:

(See footnote for a fun fact.)1

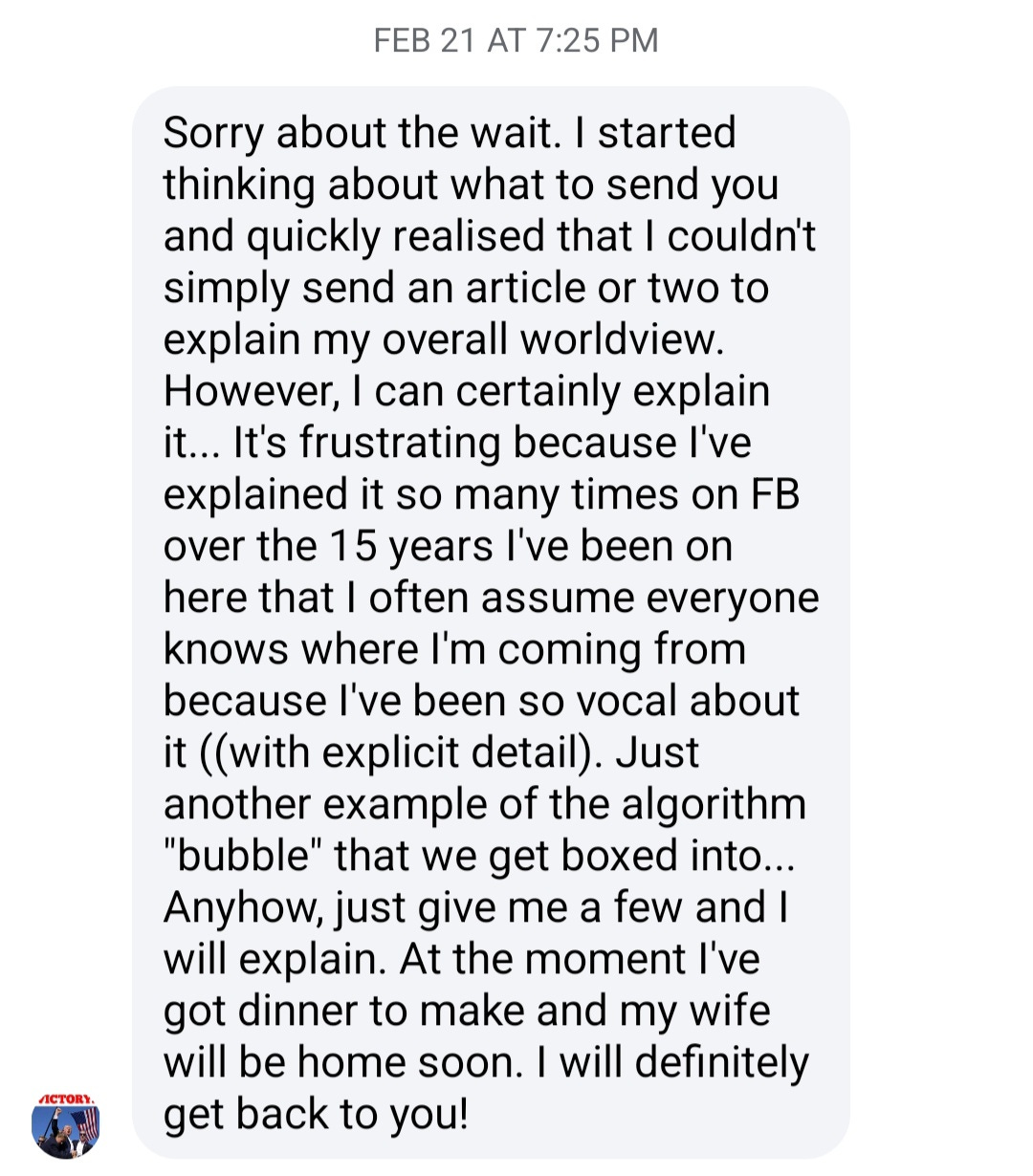

It took Fred a day to respond. My anxiety kicked in.

Was I being judged? Rejected? Ridiculed? Had I shared too much? Maybe Fred had become an anti-Semite in the decades since our childhood.

I recognized these thoughts for what they were, though: fear-based, not reality-based. I sat with the anxiety and discomfort until the next evening, when Fred responded:

Thus, our conversation rested until Fred checked back in the next night.

During the 24-hour interlude, I was inspired to write and publish on Facebook the first draft of “The World Needs a Love Revolution,” the essay that would become my inaugural Substack post.

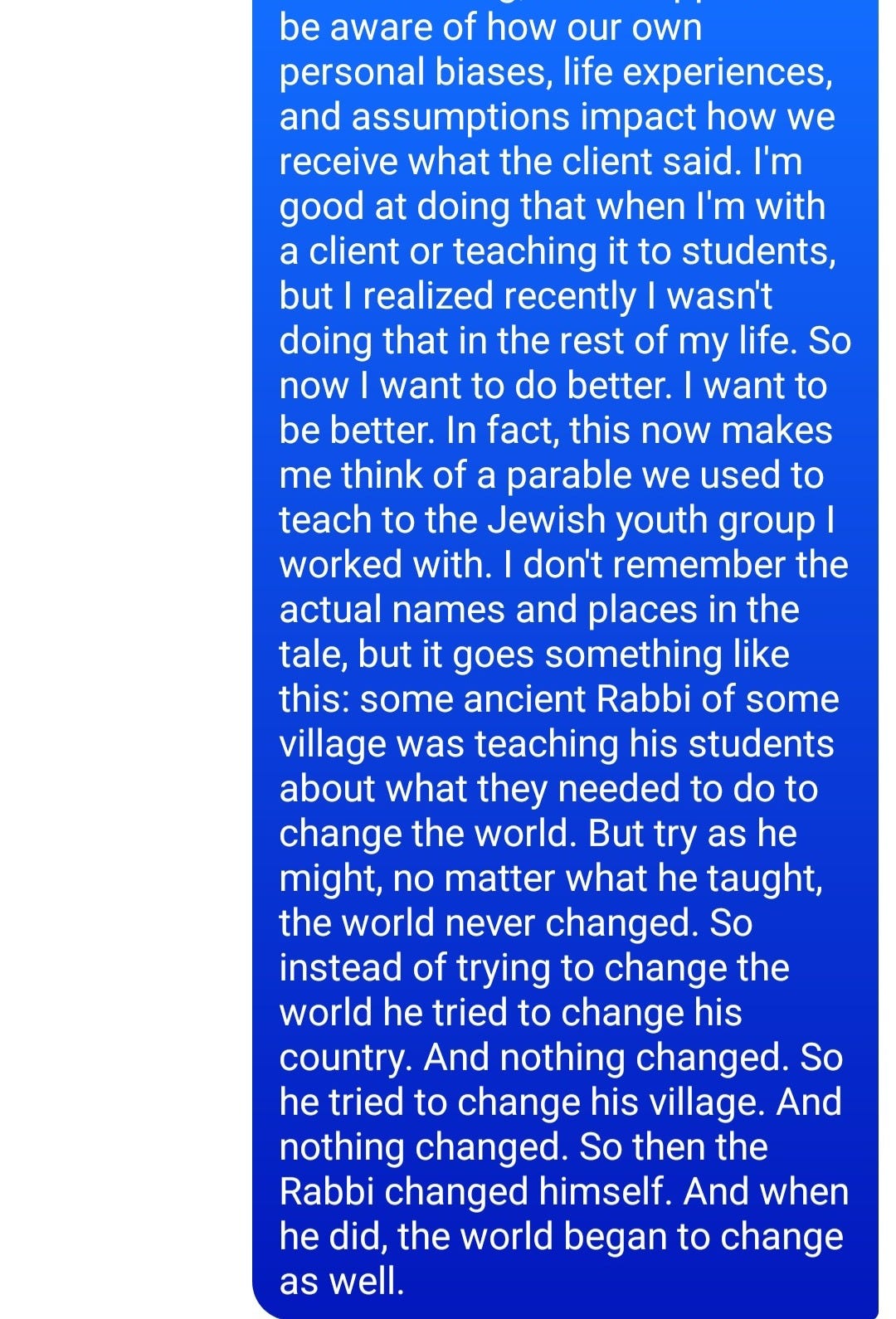

Fred’s next message to me read:

His response conveyed dignity and respect, as I wished to be treated.

The way I had treated him.

It encouraged me to continue to open up, to be authentic, and even to allow for a shift in my perspective about the legacy news media:

Fred’s response speaks for itself:

And they coexisted happily ever after.

Of course, it’s not really that simple. Is it?

Most likely not. Fred and I had the basis for building a relationship. We shared a common childhood, which served as a backdrop for our entire conversation. This was significant. It gave us a reason to trust each other.

Do I think this approach could work with a complete stranger, even if the process is more complicated?

Yes, eventually. Because it’s part of what social workers do when we build rapport with our clients. It may take weeks, rather than days, to build a safe space for communication and establish a trusting relationship, but eventually, it does happen.

As for you, my readers, many of you won’t be having these conversations with strangers, either, but rather with the estranged.

Parents, grandparents, sisters, brothers, sons, daughters, aunts, uncles, cousins, neighbors, colleagues, friends… the groundwork is already there for you to (re)connect across difference—to build a bridge of understanding, respect, and kindness.

Admittedly, it takes two, but someone must be brave enough to initiate the outreach, to extend the first kindness that clears the path for all the kindnesses to follow. Our efforts may not always be returned in kind, but we owe it to ourselves—and to each other—to try.

Because our world is a disaster right now, and it’s getting worse. And if we have any hope of fixing it, we need to remember how to stop hating each other. We need to remember to listen to each other. We need to remember how to build bridges, rather than burn them.

We cannot change hearts and minds with lectures, derision, aggression, condescension, and exclusion.

We cannot fight hate with hate. We must Lead, in all interactions, with Love.

We can and should continue to fight passionately for the causes we believe in, while simultaneously seeking to establish connection across differences.

Here are ten steps to help do so:

Invite others into discussion

Be curious in your interactions, and authentic in your approach

Treat others with dignity and respect

Have an open heart and mind

Seek to understand the other’s perspective

Be vulnerable—own your fallibility

Don’t try to change someone’s mind; create space for them to change on their own

Agree to disagree, if and when it comes to that

Part amicably

Repeat

A week later, the morning of March 1, I hit “publish” on the essay that launched Words over Swords, then headed to work.

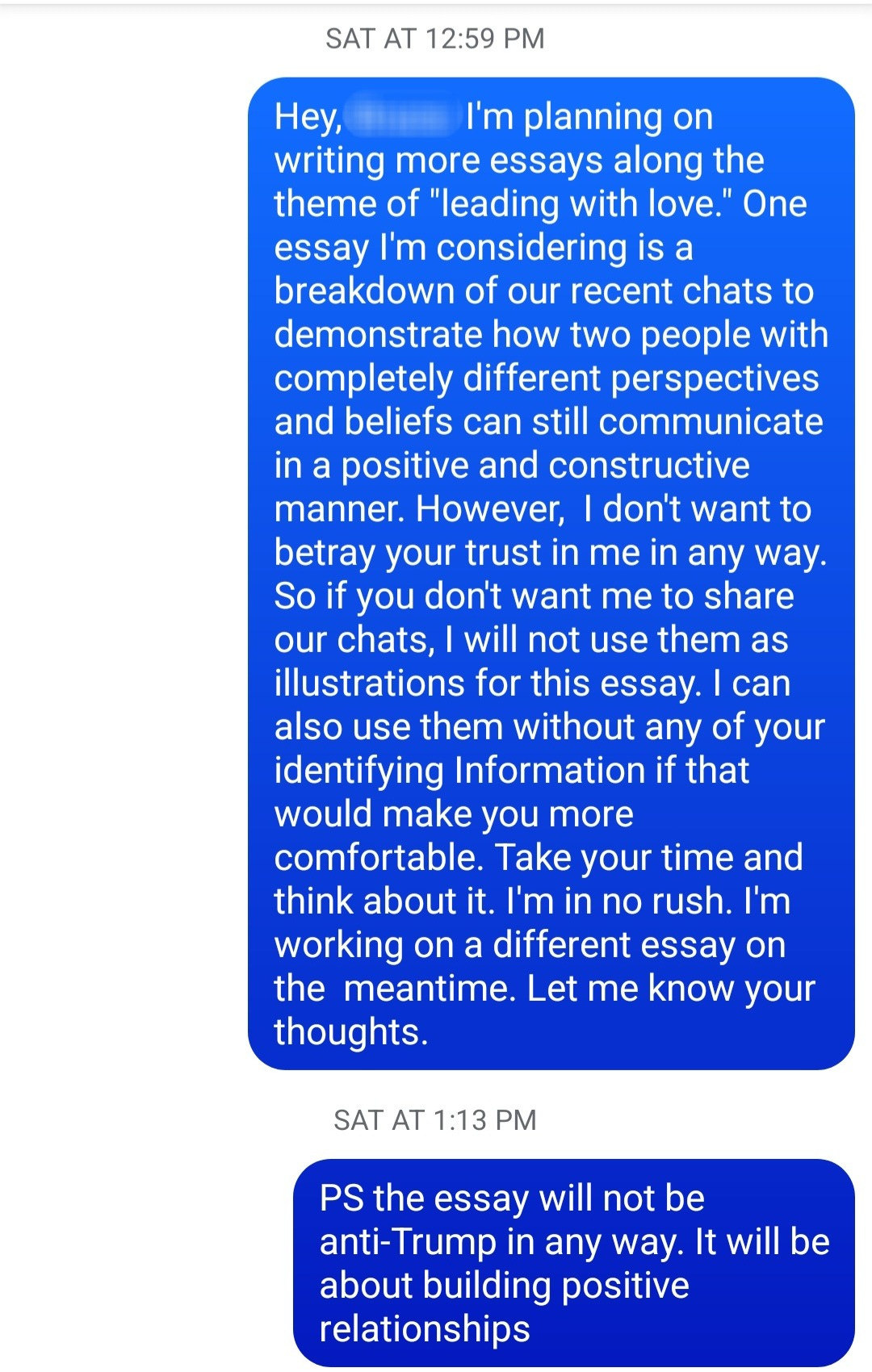

That afternoon, it occurred to me I could use my discussion with Fred as an example of how Leading with Love can transform relationships, establish connection, and bridge differences.

As a social worker, I prioritize informed consent, and again approached Fred:

His response:

The lines of communication remain open.

And as I walk on through troubled times

My spirit gets so downhearted sometimes

So where are the strong, and who are the trusted?

And where is the harmony, sweet harmony?

'Cause each time I feel it slippin' away, just makes me wanna cry

What's so funny 'bout peace, love and understanding?

References:

Costello, E. (November 1978). What’s So Funny ‘Bout Peace, Love, and Understanding [song]. On American Squirm [A]/What’s So Funny ‘Bout Peace, Love, and Understanding [B]. Radar Records.

This Week’s Moment of Unconditional Love

You met Scarlett last week. Now, meet Roscoe, the other half of Sarah W.’s dynamic Saint Bernard duo. Thanks for sharing the love, Sarah!

If you want to contribute to the Moment of Unconditional Love, like Sarah has, you can email photos of your furry friends to jeffreyafeldman2015@outlook.com. I’ll work those photos into the weekly mix, and just maybe, share a little something special about you, too.

The parable I was trying to remember at the time was a tale told of the 19th century Rabbi Yisrael Meir Kagan, also called "the Chafetz Chaim." I’ll publish it here on Substack this Wednesday.

Wow, you went there. This post is courageous and clearly took a lot of good, hard work to create. You're tackling one of the hardest things we're all facing right now, and you do so with compassion and generosity. With peace, love, and attempts at real understanding!! I like the ten tips you suggest near the end. Practical and very doable. Thanks for what you're doing (and for the sweet pet pics!).

Holy cow! This is epic! Normally I’d try to write something more profound but I don’t have it in me right now. This is beautiful, though.